Disclaimer: I don’t endorse going to Kyiv at this time. Kyiv’s relatively safe, it was my seventh trip there, and I can get around okay, but I’m still a stupid American who would have been a headache for someone if things went sideways, wasting time and resources that could be better spent on Ukrainians.

I’ve been aching for Kyiv since last February 24. It’s my favorite city in the world and there are people there whom I long to see and who want to see me, but I had no intention of going until після перемога (pislya peremoha, after victory) because I’m terribly uncomfortable with the fact that someone would need to look after me if things went sideways. I went because one friend needed a favor that literally only I could do. Since I did go, I served as a mule in both directions so that at least my visit would be of some use to some people.

Go into this knowing that all of this is through the lens of an American visiting Ukraine for the seventh time; the sixth time since the Revolution of Dignity, russia’s illegal annexation of Crimea, and the start of the war in Donbas; the first time since July 2016.

_______________________________

Getting there

Getting to Kyiv isn’t easy these days. Can’t blithely fly into Boryspil like I used to. I left my home near Washington, DC at 2:00 local time on Thursday afternoon and arrived in Kyiv at 1:15 local time on Sunday afternoon. In between were a transatlantic flight, a long layover in Heathrow’s ghastly Terminal 5 (avoid this at all costs), an overnight stay at a Warsaw hotel with a shockingly good breakfast and shockingly disappointing coffee, and an 18-hour train ride in a solo sleeper cabin (absolutely do this if you can).

I was laden. This is what I brought from DC to Kyiv.

That’s ~80 kilos/175 lbs of stuff, about 27 kilos/60 lbs of which was actually mine.

The two blue bags are full of various things donated by redditors to our partner Mykola: some tacmed, an old but serviceable drone, some winter gear, and a whole lot of electronics components for his Ghostbusters. The big black suitcase is mine, but one half of it was full of things for other people. My backpack was also only about half mine.

I’m not showing you this to say “I’m a hero!” or “Look how much stuff I carried over there all by myself!” It wasn’t hard, but it was awkward; believe me when I tell you I needed, and thankfully got, help getting it onto the train in Warsaw. (It is nonsense that a major train station has no luggage carts, WARSAW.)

I’m showing you this to illustrate how it works for people traveling between the US and Ukraine: there’s always someone on each side who needs something brought over, so we take as much as we can carry in both directions. This is one bag and about 40 pounds more than I’m used to traveling there with, but otherwise this is nothing unusual.

I was thankful to get settled into my little sleeper cabin for the long ride from Warsaw to Kyiv. I’m a little bit enamored of those train cabins. They’re so cozy and so cleverly designed! I made a short video tour to share with a group chat. I talk fast and my camera work is terrible, but if you’re interested, here it is.

I kept in touch with my friend Glib in Kyiv whenever I had signal. He asked me to tell him “when [I smelled] the war vibe in the air.” It was when I woke up somewhere near Rivne, about 7 hours after we crossed the border from Poland and I finally managed to fall asleep. I’m used to seeing Ukrainian flags and other patriotic displays all over the place in Ukraine, but this time really did feel different: don’t ask me how I sensed it from inside the train because I can’t tell you, but there was a new air of ferocity and determination that I hadn’t felt there before.

At Glib’s request, I turned on location sharing so he could track my progress. He kept me apprised as we passed through Borodyanka, then Bucha, then Irpin. russia’s brutality to each was visible through my window, sometimes at a distance, sometimes up close.

(We visited all three during my trip; that’ll be a separate post.)

Passing Borodyanka, I saw what I’m pretty sure was this building, but as a distant charred and broken mass rising from a golden brown field under a crisp blue sky. And I learned something: for me, the emotional impact of the photos we see is blunted by the fact that the subjects are divorced from their surroundings. Only when I feel the entire space around me can I appreciate the destruction for the wound it is. It’s obscene, out of place, shocking the way a raw hamburgery wound on a clean limb is shocking. It places the evil in a way that photos never could: the evil came here, to this apartment building whose residents looked out over a grassy plain stretching to a far horizon, an occasional train chugging through in the middle distance.

It was a jolt, and every damaged building and courtyard I saw as we rolled through Bucha and Irpin toward Kyiv jolted me again. Writing and proofreading this almost two months later, I still need to pause and sit with it for a few minutes before moving on.

There’s no graceful way to segue out of that somber recollection to my joyful arrival in Kyiv, so I won’t try.

_______________________________

And then I was in Kyiv!

The camera is my enemy, especially after 3 straight days of travel.

Glib and Mykola met me at the train: Mykola to grab his bags and Glib to pick me up and hand me the first cup of good, non-airport, non-airplane, non-Polish-hotel, non-train coffee I’d had in three days. Guys, I appreciate you both. I could’ve done it without you and the coffee, but I’m grateful that I didn’t have to. Дякую вам обом.

When I go to Kyiv, I usually stay in the same room in the same hotel right on Maidan Nezalezhnosti (Independence Square, often simply called Maidan). I broke with tradition this time and got an 8th-floor apartment on Kyiv’s main drag, Khreshchatyk, just across a skinny side street from Maidan. The view from my bedroom and kitchen was a sight for sore eyes, balm for a sad soul, so thoroughly Kyiv that I spent an inordinate amount of time just staring out the window and taking it in.

This post isn’t a travelogue and I’m not going to bore you with all my photos, but I have to share these two because they make my heart sing.

Thanks for indulging me. Let’s get to the stuff you want to know.

_______________________________

So what’s it like in Kyiv these days?

I won’t go into any detail about, or show any pictures of, defenses. They’re around. Some I knew to expect. Some surprised me a little.

The war is present. On the shortish drive from Kyiv-Pasazhyrskyi, the city’s main train station, to my apartment on Khreshchatyk, Glib pointed out a dozen or more buildings showing damage from russian strikes. This energy company building. Down that street, the beautiful old residential building where the rocket killed the pregnant woman. Off to the right, the first residential building that was hit.

Nothing I saw looked as forsaken as some things we saw in Borodyanka and Irpin. (That’s another post for another day.) There are some blown-out windows here and there, some plywood, but nothing was left charred and open to the elements.

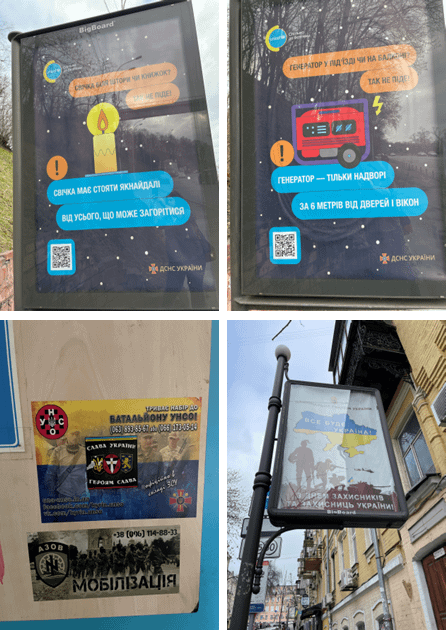

Kyiv is dotted with rectangular lightboxes that usually show ads. (Though I’ve also seen them used to welcome the Scorpions to the city.) Most of them, at least in the center, now bear patriotic messages, suggestions to avoid setting your dwelling on fire and other useful wartime tips, and recruitment ads. You can also find recruitment stickers plastered all over the place.

Directional signs in the city center–Maidan Nezalezhnosti this way, Golden Gate that way, and so on–have been spray painted over (with varying degrees of success, but the intent is there). Street signs have been taken down, too. It was a relief when I realized I hadn’t lost all my bearings and can still get around the center, at least, without them.

(Except when I had a forgetful moment in the Maidan metro station and couldn’t remember which train to take to Golden Gate. As I stood there all bewildered, I heard someone call my name, which was briefly even more bewildering because I don’t have that many friends there. It turned out to be Mykola, in possibly the most perfectly timed appearance of his life. It couldn’t have been scripted better. If you ever find yourself unable to remember how to get from A to B on Kyiv’s metro, Mykola is exactly the man you want appearing out of nowhere.)

Night is quieter now. When I was there, curfew was from 11 pm to 5 am. Restaurants closed at 9 or 10 so the staff would have time to close up and get home before curfew. Khreshchatyk remains its lively, noisy, buskery, street dancery self, but only until about an hour before curfew, when everyone packs it in and quiet descends. I prefer quiet in general, but I found it a bit sad. The racket of Khreshchatyk is part of the Kyiv soundscape for me. But it came with one big compensation: Aroma #@%&ing Kava, which plays unnecessarily loud music directly outside hotels at 4:00 am, can’t now. Take that, Aroma Kava!

My buddy Maxim–you’ll hear about him in Part II–told me he thought I’d be shocked by the number of soldiers I’d see. I kind of dismissed it; I’d been there several times since the war started in 2014 and I’m used to seeing uniformed soldiers all over the place. He also said he’d thought I’d find it reassuring. He escaped Nova Kakhovka in southeastern Ukraine, which has been occupied since day 1 of the full-scale war. After the russian soldiers on his own streets, the Ukrainian soldiers on Kyiv’s were a comfort to him. I replied that I thought I’d find it sad, because it means a place and some people I love are in danger.

He was right on both counts. The military presence there is on a whole other level now, and it really is reassuring to see.

Air raid alerts are a fact of life now, of course, and I was interested to see how the city reacted. Turns out that life goes on pretty much as normal. I’d hear the siren–unless I was asleep, or in the shower, or listening to music … so pretty much only if I was outside or standing at the window with no other noise–or see the alert on my phone, and then watch as people just sort of went on about their business. People do still shelter, but not in such numbers or for such durations as they did in the early days of the full-scale war.

Kyiv, in short, has adapted to its circumstances and forges ahead.

In Part II, I’ll tell you a bit about what I did there.